By Joce Sterman, Daniela Molina, Jon Decker, Jamie Grey, Yelta Reyna, Hannah Lorenzo, Samantha Latson, Lizzie Wright and Lauren Truex.

Portland, Ore. (InvestigateTV) – As the mother of three young boys, life for Oregon mom Edith Goodwin is always unpredictable.

Her children, she said, have unique personalities that require different skills to manage. That’s not just true with how they play, but also how they learn.

For Goodwin and her oldest son, Joseph, it hasn’t been easy. She’s spent most of her life fighting to get him special education services through the public education system.

Goodwin’s struggles happen across the country because of disparate polices, an InvestigateTV analysis found.

(L-R) Elijah, Isaiah, and Joseph sit down together outside while Joseph is reading a book. Mom, Edith Goodwin makes sure her kids aren’t falling behind in school.

As a toddler, Joseph was diagnosed with a speech delay in Colorado where the family was living at the time. Goodwin tried to get him services at a local preschool, and although he qualified, she wasn’t satisfied with the process and opted for private speech therapy instead.

Diagnoses for ADHD and autism soon followed for Joseph, as the family moved for work. But the family’s challenges with the special education system were just beginning.

When they later moved to New Mexico, Goodwin quickly realized eligibility for special education in that state was different.

“They looked at the records and they just looked at the bottom line, at the scores, and said he wouldn’t qualify,” Goodwin said.

The scores that once qualified Joseph for services in Colorado were no longer acceptable in New Mexico. The school, Goodwin said, told her there wasn’t a need to put him in special education because of his performance on the assessment.

“He was very intelligent. He was a leader,” Goodwin said. “He was well-liked in school, so they didn’t recognize a need with him, but he was struggling and falling behind in reading.”

When the family moved yet again to Idaho, Goodwin’s struggle continued. Seeking advice, she turned to Facebook groups to ask how other families navigated the state’s system.

“They recommended getting in touch with an outside person that could teach me how to communicate with the school,” Goodwin said. “They couldn’t go with me to the classroom or ask or advocate for me, but they taught me how to advocate.”

Using those skills, Goodwin requested an evaluation for Joseph, but was ultimately denied.

“I did it by the book, and they still refused,” Goodwin said. “And so, then I took it to the next level by filing a complaint with the state.”

That complaint resulted in mediation, with Joseph eventually getting a full evaluation by different specialists.

In the end, it took Goodwin six months to get her son the services he qualified for under the state’s special education policy. That battle is among the many documented in a binder she’s used for years to track her efforts to obtain services for Joseph from state to state.

In Oregon, following yet another move, Joseph qualified for services with ease. But in Colorado again, the state required a repeat evaluation because it wouldn’t accept the one done previously in another state by Joseph’s doctor.

That was all before the family returned to Oregon once more.

“If they could have just used the information they already had and applied it, they would have been just fine. It was a lot of time that was wasted that could have helped my son,” Goodwin said. “I felt like at times maybe I was failing them as a parent because I was trying to advocate for them. I was trying to do it. And yet no matter how hard I tried, it still wasn’t helping.”

Policy breakdown

The Department of Education has long watchdogged special education programs across the country.

In the 2020-2021 school year, data from the National Center for Education Statistics showed more than 7.2 million students between the ages of 3-21 received special education services under a federal law known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

Total Number of Students Receiving Special Education Services

Those stats show California, Texas, New York, Florida, and Pennsylvania were the states with the highest number of special education students enrolled as of the 2020-2021 school year.

In those states, and others, parents like Goodwin have been forced to learn how to navigate a complicated system, discovering access to special education services can vary greatly depending on their state’s eligibility criteria.

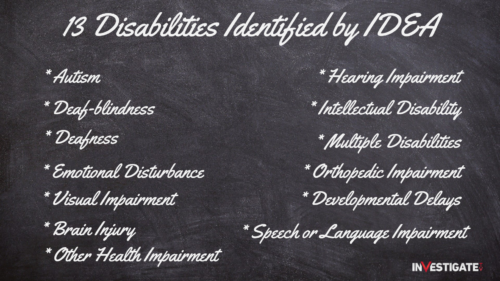

Eligibility for services is largely dictated by specific disabilities outlined in the law. IDEA guarantees that students with one of 13 disabilities have access to free public education with appropriate accommodations.

Those disability categories identified by the federal government under IDEA are: Autism, deafness-blindness, deafness, emotional disturbance, hearing impairment, intellectual disability, multiple disabilities, orthopedic impairment, other health impairment, specific learning disability, speech or language impairment, traumatic brain injury, visual impairment, and developmental delay.

A graphic with 13 IDEA-identified disabilities.

The law allows states to create their own special education policies based on the federal IDEA framework. As a result, states can determine their own processes for identifying children for services and the evaluation criteria to meet those requirements.

To understand the variations between special education policies across the country, InvestigateTV and the Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism at Indiana University did our own audit, requesting and analyzing the special education eligibility and evaluation policies from all 50 states.

Our analysis found major disparities from state to state, with each one determining its policies through a series of classifications: disability, age, maximum evaluation time and implementation time, and whether a medical assessment, school assessment, or both qualify as support to eligibility.

Among the findings:

• In South Dakota, there are specific measurements that qualify individuals with deafness or hearing loss for services. But just across the border, Nebraska’s policy has “flexibility” and states that any child with hearing loss of any degree might be eligible for services.

• In Michigan, children can get special education services up until age 25.

• In Connecticut, a parent only has to wait a maximum of 45 days to get their child evaluated and placed with an IEP (individualized education program). In West Virginia that process can take a maximum of 110 days, nearly four months.

While parents wait for a team formulated by the school to decide whether their child qualifies for services, states can also determine whether additional material can be used to make final decisions — that includes medical assessments.

InvestigateTV looked closely at the differences in which material is deemed acceptable for evaluation and found:

• Eighteen states don’t accept a medical assessment done by a physician. The remaining states may use those assessments as part of the final decision process, but isn’t guaranteed.

• At least 25 states accept both medical and school assessments to help with student evaluation, including Colorado, Louisiana, Mississippi, and North Carolina.

In a 2019 Government Accountability Office report, the government watchdog looked into the variation of services offered in different states and found many examples.

“In Maryland, a child must have at least a 25 percent delay in one or more developmental areas to be eligible for Early Intervention services, while in Arizona, a child must demonstrate a 50 percent delay in one or more developmental areas to be eligible,” the GAO report said.

For parents like Goodwin, who have navigated the special education system, the patchwork of policies from state to state was surprising.

“You shouldn’t have to go, move from county to county and fight each school system,” Goodwin said. “It’s supposed to be a federal program. It’s supposed to be uniform. It’s supposed to be services that they are entitled to have nationwide.”

Department of Education perspective:

Katy Neas, deputy assistant secretary of the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, said the differences we uncovered are a reflection of the intent of IDEA, which was designed as a framework for states, which can then meet their obligation to provide special education in ways that work most effectively for them.

Neas emphasized that children in special education have complex and unique needs that should be addressed with individual approaches. That, she explained, takes a commitment to serving children in special education that hasn’t been universal.

“If we could change attitudes that would be by far the most important thing we could do. And you only do that when you can show people what success really is,” Neas said. “You can talk about it in lofty terms but until you take somebody by the hand and show them, see this child, see the progress this child has made, see the people who have come together to support this child. Once you show them what it looks like, they think, ‘Oh, I can do that too.’ And so I just really think we need to show people what’s possible.”

Katy Neas, the deputy assistant secretary and acting assistant secretary of the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services (OSERS), walks through the office at the U.S. Department of Education

Neas was clear, uniformity when it comes to implementation of IDEA isn’t the goal. But in some areas, including wait times for evaluation, Neas said there shouldn’t be vast differences. The delays we uncovered, she said, are concerning, telling InvestigateTV states should have a sense of urgency when it comes to identifying students who need special education.

“The thought of making a child and a family wait in order to get the services their child needs that’s going to influence the rest of their lives, it’s just not acceptable,” Neas said.

Implementation of IEPs

Ana Brannan has been studying special education for years.

As an associate professor in the Special Education program at Indiana University’s School of Education, she has specialized in children’s mental health services.

Brannan’s interest in the special education field developed from her childhood. Having family members with special needs, she found an appreciation for helping educate people who may require services at an early age.

“I am the middle [child] of seven children so from as soon as I could walk, I was helping other little babies walk. I knew by the time I was 12, I was going to do something with kids,” Brannan said. “Over the years I just met more people who had disabilities and there’s a fair few in my family.”

But Brannan’s experience extends beyond her family. She’s seen firsthand how state formulas determine special education eligibility for children. She says some states start with basic screenings, while others use an IQ test.

“There’s a lot of variability across states,” Brannan said. “There’s also variability within states, and one of the reasons is because of resources.”

Ana Brannan, an associate professor, works in her office at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana.

The variability also extends to compliance with meeting the requirements of IDEA. Although the law has been in place for more than 40 years, many states still fall short of the government’s expectations.

In a report to Congress last year, the Department of Education put more than 20 states and Washington D.C. on a list noting they “needed assistance” meeting IDEA for two or more consecutive years.

Two additional states, New York and Vermont, were classified as “needing intervention”.

Brannan said the states that struggle to meet special education requirements do so because of myriad factors including a lack of funding, teacher shortages and a culture that doesn’t always acknowledge the importance of providing special education services.

“Across the country, there are not enough resources in schools for kids. For kids with disabilities, even more so,” Brannan said. “I think that is a challenge for all of us.”

Families’ experiences receiving special education services

Discovering that a child has challenges in the classroom may happen as a result of close communication with teachers.

That’s one of the reasons that schools across the country implement the “Child Find” initiative, which gives teachers a pathway to highlight students that might need special education assistance. Parents can then give approval to have their children evaluated for services.

Phoenix mom Melissa Grant says her son was diagnosed with ADHD and dyslexia in the fourth grade. He was in kindergarten at Deer Valley Unified School District when his teacher recognized he might benefit from special education.

“I thought it was really an interesting start to the whole process because his kindergarten teacher was the one who was raising the flag, saying, ‘There’s something going on here’,” Grant said.

Another Deer Valley parent, Jillian Jones, had a positive experience with the teachers working with her son, who was diagnosed with dyslexia in grade school.

She now partners with faculty at DVUSD to create those positive experiences for other families who may need services.

Jones leads the Parents of DVUSD Students with Special Needs, a Facebook support group, which has 336 members.

The group offers general information and advocacy support for parents in special education and holds fundraising events for children with learning difficulties. It’s similar to the group Edith Goodwin joined when seeking assistance securing services for her son, Joseph.

Rising Special Education Teacher Shortage and Implementation

Nearly half of all public schools reported part-time and full-time teaching vacancies in 2022, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Those numbers also impact special education teachers.

“Many teachers experience burnout and stress trying to meet the needs of their students in special education,” said Terry McDaniel, an Indiana State University professor and supervisor of the annual survey of Hoosier school superintendents.

McDaniel said that the COVID-19 pandemic and virtual learning only exacerbated that trend.

“In Indiana, despite the efforts of the states’ DOE and the legislature to encourage people to pursue special education, the shortage only continued to increase,” McDaniel said.

McDaniel said 2021 had the highest teacher shortage rate in seven years in Indiana, with 96.5 percent of the districts surveyed reporting that they had trouble finding teachers.

“Trying to find special education teachers is very, very difficult,” McDaniel said.

Kelly Myers, a special education teacher at Greater Clark County Schools in southern Indiana, which is among the state’s largest districts, reported that more students are being put into co-taught classes than desired.

“Due to the lack of staff, more students from general education are being placed into the resource group with around 15 to 16 students instead of the usual 10 to 12,” Myers said. “Larger classes make it more difficult for teachers to meet the needs of all their pupils.”

Funding special education

Experts and the federal government itself recognize the lack of funding is problematic for special education.

When the government enacted IDEA in 1975, the legislation came with a commitment to fund 40% of the average cost per special education student, but that promise hasn’t been kept.

As of 2020, only 13.2% of the cost of special education has been covered according to the National Education Association (NAE), a labor union. In Washington, D.C. alone, the NEA says the funding needed to fully cover special education falls short by more than $61 billion.

Neas, with the Department of Education, said states have an obligation to cover the majority of the cost of special education. But she insists Congress also needs to step up to the plate in a more significant way. “We’re going to pay for the needs of these individuals one way or the other. And if we give kids more opportunities in school, they’re going to be independent adults. They’re going to need less support throughout the rest of their lives,” she said. “I kind of feel like, pay me now or pay me later. The investments we make in education for students with disabilities, we will reap the benefits of that for decades to come.”

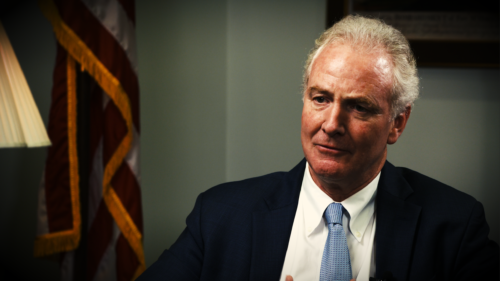

Some members of Congress are already trying to answer that call to provide more funding. Last year Senator Chris Van Hollen, D-Maryland, and Congressman Jared Huffman, D-Calif., introduced the IDEA Full Funding Act.

The legislation would offer permanent and mandatory funding to grant programs to help states and other underlying areas for special education and related services for children with disabilities.

“I think that the fact that the federal government has shortchanged schools and not met this commitment, has meant the local schools throughout the country also are shortchanging students in their budgets,” said Van Hollen. “And the impact is felt by kids with disabilities.”

Sen. Chris Van Hollen, D-Maryland, talks about special education funding in his office on Capitol Hill.

Van Hollen said the bill would mean more special education teachers and significantly more resources in the classroom to help children with disabilities. The bill currently sits in the House.

If the legislation passes, it would alleviate some of the burdens. But challenges remain in the special education system, with training for educators among some of the most pressing issues.

Morénike Giwa-Onaiwu, a mom and a special education advocate in Texas, said she thinks all teachers should have some sort of special education training regardless of their discipline.

Without that, she says parents have to figure out the system on their own. For Giwa Onaiwu, she faced her own hardships as an adoptive and biological parent of children on the spectrum.

“Trying to navigate special education was just so overwhelming,” Giwa Onaiwu said. “It felt like some kind of game of whack a mole.”

She often felt like she had to Google terms and find the information herself.

“I felt like I spent more time looking things up to make sure they weren’t getting something over on me for my kids than anything else and I said ‘Wow, I don’t want anybody else to go through this,” Giwa Onaiwu said.

She now uses her experience to help advocate for less isolation among special education students and help create a more inclusive environment.

After spending years navigating the special education system, mom Edith Goodwin believes more needs to be done to help families whose children may experience learning difficulties. And she’d like to see more uniformity in the process of obtaining services, so geography isn’t a factor.

Joseph (blue and yellow jacket) and his two brothers spend some times in the woods looking at nature climbing this rock. All three boys are achieving their educational goals.

Her son, Joseph, is once again enrolled in programs she firmly believes are helping him achieve his educational goals. But she worries about what will happen if the family has to move again.

“They’re getting a great education here in Oregon,” Goodwin said. “But if you go to another state, we’ll have to do the process all over again, just because they were in school and just because there is special education that doesn’t guarantee an education.”

Additional reporting by Hali Tauxe, Ryley Ober and Kayan Tara.