By Jill Riepenhoff and Joce Sterman

(InvestigateTV) — Kimberly Haven’s punishment for a crime committed in Maryland was only supposed to involve serving time behind bars. She said it ended up costing her her uterus.

After she was incarcerated and sent to a prison psychiatric unit, Stacy Burnett said she was forced to bleed on herself throughout her menstrual cycle because she was not allowed to possess underwear, toilet paper or feminine hygiene products.

In times of desperation, women behind bars often fashion feminine hygiene products out of bedding, socks and even pages from the Bible.

“MacGyver is the patron saint of prisons. You have to take what you have and make do,” Burnett said. “It’s a constant struggle.”

Incarcerated women have used unconventional — and highly unsanitary — items because their requests for pads or tampons were delayed or dismissed altogether.

In some of the most extreme situations, incarcerated women have been forced to trade sex for a tampon.

Many states lack laws or written policies to provide incarcerated women this basic need — meaning for many the struggle to find or fashion the necessary products is a monthly struggle.

“Every single woman I talked to, no matter where they’d been in prison or how many years it had been since they’d been released, every single one of them said, ‘I felt like they had to beg like a dog to get what I needed,’” said Miriam Vishniac, a post-graduate researcher studying access to feminine hygiene products behind bars.

Vishniac created The Prison Flow Project, which advocates for access to period products and serves as both a database of resources for incarcerated women and their loved ones.

She said she became interested in the topic about a decade ago.

Academic research Miriam Vishniac has spent years researching menstrual product access behind bars, eventually creating the Prison Flow Project. Photo credit: Scotty Smith, InvestigateTV

“There was a news story from Kentucky where a woman had been sent to court without pants, and it turned out that she had stained them with menstrual blood and hadn’t been given any other clothing,” Vishniac said. “I started seeing at the same time more reporting on what was happening and like more reporting on women having these issues in prison. And it didn’t seem like there was an academic look and trying to gather information and sort of trying to really put together what exactly is happening here because it seems like there is a problem.”

As of January, only 31 states had a law or a written policy to address feminine hygiene products in prisons, according to an InvestigateTV analysis.

The analysis found that few of these laws or written policies guarantee access to all the types of products women behind bars may need, or that products will be made available at all times of the day or night.

It’s a disheartening reality even to some who lead prisons.

“To deny a woman basic hygiene ideally is indecent, is a violation of their rights,” said Geneva Holland, warden of the Maryland Correctional Institution for Women. “We believe (in) and we want to maintain their dignity.”

The analysis found that few of these laws or written policies guarantee access to all the types of products women behind bars may need, or that products will be made available at all times of the day or night.

It’s a disheartening reality even to some who lead prisons.

“To deny a woman basic hygiene ideally is indecent, is a violation of their rights,” said Geneva Holland, warden of the Maryland Correctional Institution for Women. “We believe (in) and we want to maintain their dignity.”

Geneva Holland, warden of the Maryland Correctional Institution for Women, says incarcerated women in the facility she oversees receive menstrual products upon arrival, every two weeks and upon request. Photo credit: Scotty Smith, InvestigateTV

Make-shift mayhem

Maryland passed a law in 2018 to ensure that incarcerated women have a sufficient supply of feminine hygiene products at all times.

After she was released, Haven was part of the effort to pass that bill.

Without access to necessary products, Haven said she often fashioned the sanitary pads provided by the prison into tampons — and even sold them to other women.

Homemade tampons are inherently dangerous, however: The type of materials used, the environment and the handling of them can all introduce bacteria.

Even sanitary pads, when pulled apart, create risks as the often synthetic fibers become airborne.

Haven was diagnosed with toxic shock syndrome — a rare but potentially life-threatening complication from certain bacterial infections.

She blames the use of makeshift tampons during her incarceration.

“They go up inside you,” she said. “So as a result of that, I ended up coming home and having to have an emergency hysterectomy.”

Haven said it wasn’t only her own experience that led her to advocacy.

“I’ve watched women wad up toilet paper. I’ve watched them use washcloths,” she said.

Advocate Kimberly Haven says she’s fought in at least five states for the passage of legislation designed to improve menstrual product access for incarcerated women. Photo credit: Kimberly Haven

When pushing for the passage of the 2018 bill, she showed her makeshift tampons to Maryland lawmakers and told the horrors of what can and does happen.

“We’re … talking [reproductive] sterility. We’re talking infections. We’re talking all of that we then have to pay for on the back end when, if we could just do the right on the front end, we would be much better served,” she said.

Maryland’s law requires each correctional facility in the state to create a written policy addressing feminine hygiene and requires them to provide tampons and pads for free on a routine basis and as needed.

But that is not the case in every state.

InvestigateTV and the Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism at Indiana University analyzed existing state laws and policies and found only nine states have language in place that provides incarcerated women access to period products at any time.

Less than two dozen states detail the types of feminine hygiene products — such as pads, tampons, menstrual cups and panty liners — that will be made available.

“The problem is that without specifics you leave a lot of it up to individual wardens, individual guards, and there’s no understanding of how important the specifics are,” Vishniac, the academic researcher, said.

Some states provide only sanitary napkins. Some limit the number of supplies women receive each month.

All of this implies that every woman has the same menstrual cycle, flow and duration, Vishniac said.

Additionally, many state laws and policies require products be made available “upon request.”

Critics such as Haven and Vishniac said that can weaponized against the women.

For example, U.S. Justice Department investigations of prisons in Alabama, Florida and New Jersey found that women who asked for supplies were expected to perform sex acts in exchange for a period product, court records show.

Failures by states, lawmakers, wardens and jailers to properly address a biological function that women cannot control only serves to dehumanize them, critics said, and the ramifications can extend even beyond a facility’s walls.

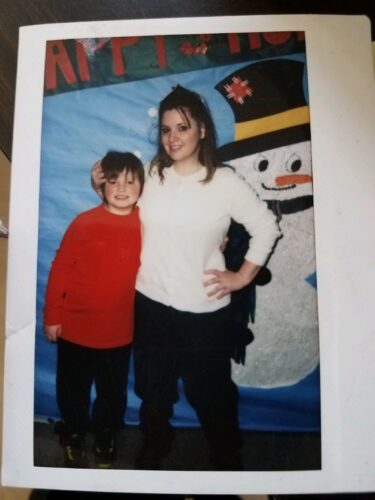

Upon her release, Burnett also became an advocate. She said she wants those in charge to realize how difficult such treatment can make it to return home with their dignity intact.

“They need to look at that and not exclude people who are incarcerated that somehow when they hit the prison gate, that they have abandoned all of their civil rights or turned in their humanity card,” she said. “If anything, we need a little bit more understanding and support so that we can come home and be functioning, contributing members of society.”

Stacy Burnett says a series of mistakes during post-partum depression she experienced following the birth of her son led to her incarceration. Today she advocates to help other women who have been part of the correctional system. Photo credit Stacy Burnett

Begging for supplies

InvestigateTV and the Arnolt Center sent dozens of public record requests to state prison systems and local jurisdictions for complaints related to feminine hygiene.

Records show, at best, examples of indifference to the women’s problems when they asked for supplies.

In Las Vegas, one woman asked an officer for a pad who responded: “Would [she] like her to pull one out of her a**?”

Also in Las Vegas, a correctional officer was disciplined after she told a jailed woman that she could only request sanitary pads during lunch or dinner.

In the Cleveland area, a woman who couldn’t use pads because of skin irritation had to wait nine days for tampons. In New Orleans, a woman had to wait for six days for access to period products.

In Tyler, Texas, a woman complained that she had been “begging” for toilet paper, tampons and pads for hours. She said she had used the last of her toilet paper as a pad and had to resort to using her socks.

Nevada and Ohio don’t have a state law regarding feminine hygiene in prisons and jails, and Texas’ law applies only to state institutions — not local jails where the woman in Tyler was confined.

To Holland, the warden in Maryland, such complaints illustrate the importance of clear laws and policies.

“We can’t predict when they need them. We can’t predict their flow. Some women have medical issues. So, it’s very important that we make sure they have what they need at all times, especially when it comes to feminine hygiene,” she said.

Holland said she believes other states and local jurisdictions should follow Maryland’s lead.

“They are already in prison. They’re already serving their time. That’s an additional punishment to not give them their basic needs — punishing them all over again,” she said. “And they’ve already been tried and sentenced for whatever crime they committed.”

After successfully helping pass the Maryland law, Haven is now executive director of Reproductive Justice Inside and is pushing for laws in other states.

Some call her the “Tampon Queen” — others use an unflattering term — but she said it doesn’t matter to her what she’s called as long as things change.

“If telling my story and the work that I’ve done around this issue is going to drive change, then yeah, I’ll wear it was a badge of honor,” she said.

Associate producer Mackenzie Bruns and the following students from the Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism at Indiana University contributed research to this report: Olivia Bianco, Mina Denny, Wyatt Lambert, Haley Miller, Nadia Scharf, Emma Walls and Jasmine Wright.