By Jill Riepenhoff, Joce Sterman, Meredith Hemphill, Ryan Murphy, Maddie Maloy, Julia Pearl, Mackenzie Lionberger, Tatum Hanson, Ashton Hackman and Sammi Bilitz

InvestigateTV – Every year, for the past six decades, at least one student has died or suffered life-altering injuries in a hazing incident.

The majority were college students pledging a fraternity.

Across the country, uncounted lawsuits, police reports, universities’ records and media accounts tell the harrowing details of initiation rituals that have left hundreds of students seriously injured, or worse.

Last year, Rutgers student Armand Runte fractured his skull and suffered serious brain injuries after drinking “life-threatening” amounts of alcohol then falling down a flight of stairs at a fraternity house, according to a lawsuit he filed in October.

In 2021, Danny Santulli was left unable to walk, talk or see after a fraternity event at the University of Missouri in which his attorney says he was required to drink, among other things, a bottle of vodka. His family has filed a lawsuit.

Stone Foltz, a pledge at Bowling Green State University in Ohio, died in 2021 as a result of chugging a bottle of bourbon “in as little as 18 minutes,” according to a lawsuit filed by his parents.

In 2017, hazing led to the deaths of Maxwell Gruver at Louisiana State, Andrew Coffey at Florida State, Matthew Ellis at Texas State and Timothy Piazza at Penn State, lawsuits show.

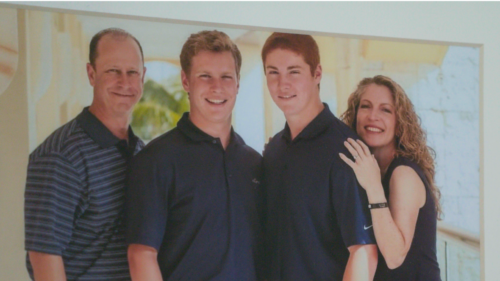

“You never think you’re going to be the people on TV. This happens to other people, not us,” said Evelyn Piazza, whose son died after a 2017 event at a Penn State fraternity that garnered national headlines for its shocking brutality. “And now we’re on TV.”

A Piazza family photo shows the New Jersey natives in happier times before they became vocal advocates for change after a hazing incident claimed the life of their youngest son, Tim. Pictured, left to right, Jim, Michael, Tim, and Evelyn Piazza.

On the first night of pledging at the Beta Theta Pi fraternity, 19-year-old Timothy Piazza went through an alcohol-fueled obstacle course known as the gauntlet, according to the family’s lawsuit.

After surviving the drinking contest, Piazza, who was heavily intoxicated, fell down a flight of stairs and was knocked unconscious. Fraternity members moved him to a couch then largely ignored him for hours.

He later died at a hospital.

Several members of the fraternity faced criminal charges, with many ultimately convicted of minor crimes related to alcohol and hazing. Penn State banned Beta Theta Pi from campus. The Piazza family pushed for new state laws to make hazing a felony in cases of serious injury or death and to make reporting of hazing incidents transparent.

And yet five years later, others continue to follow Piazza’s tragic fate.

“Hazing, the word, is treated lightly. It really is abuse,” Mrs. Piazza said.

Seven of the nine of the fraternities involved in death cases that are named by InvestigateTV issued statements denouncing hazing. The full statements are at the bottom of the page. Delta Chi, whose chapter at Virginia Commonwealth University had a death, and Sigma Pi, whose Ohio University chapter had a death, did not respond to requests for comment.

Hazing on college campuses claims lives and injures and humiliates countless others, yet government officials fail to enact strong laws to curb the persistent problem.

InvestigateTV analyzed state hazing laws from StopHazing.org, a nonprofit that tracks legislation and advocates for change, and found a patchwork of regulation that has done little to end annual initiation rituals of physical, mental and sexual abuse.

Only 15 states make hazing a felony of its own in cases of death or serious harm. For example, if a pledge who is forced to drink at a fraternity in Kansas and later dies of alcohol poisoning, its law doesn’t expressly make hazing a felony. But in neighboring Missouri, students can be charged with a felony, which can lead to prison sentences.

Twenty-two states don’t require schools to craft anti-hazing policies, which define for students what is not acceptable behavior.

Six states don’t have any anti-hazing laws in place: Alaska, Hawaii, Montana, New Mexico, South Dakota and Wyoming.

In Minnesota and Utah, the hazing law applies only to high schools.

In the wake of Maxwell Gruver’s death at LSU in 2017, Sen. Bill Cassidy, a Louisiana Republican, began pushing for a federal law to address hazing.

Gruver and other pledges had to chug 190-proof liquor when they gave wrong answers to questions about the Phi Delta Theta fraternity or could not recite the Greek alphabet, the Associated Press reported.

Gruver died from acute alcohol intoxication.

“This is effectively a public health issue,” said Cassidy, who also is a physician.

And yet Cassidy’s legislation remains untouched by Congress.

“We just need everybody concerned about the issue to join with us,” he said. “You can’t imagine what parent thinks when she sends her child off to school, that she’s going to get a phone call in the middle of the night, not about a car wreck, not even about a suicide, but about something which was so avoidable.”

Louisiana Sen. Bill Cassidy talks about anti-hazing legislation he’s introduced in Congress from his office on Capitol Hill.

A researcher tracks the deadly toll of hazing

By Hank Nuwer’s calculation, hazing has claimed at least 285 students, with the first fraternity pledge dying in 1873 at Cornell University in New York.

Huwer, a journalist and college professor, began researching the issue in 1975 after witnessing a hazing incident involving a rugby club when he was a teaching fellow in Nevada.

“I saw their initiation in a bar, and it was pouring alcohol down the throats of pledges,” he said. “They used Everclear,” which is 95-proof grain alcohol and then lit a match.

One pledge was badly burned.

“This was definitely a turning point,” he said. “Before, I thought hazing was stupid and that this time I realized how dangerous it was.”

He set out to create a database of all the victims of hazing, likely the most comprehensive accounting of the deaths, and has written five books on the issue.

Through his research, he has discovered that between 1959 and 2021, hazing has killed at least one student every year – all but six of them were college students.

Nuwer knows the name of every student who has died and can rattle off even the smallest details about these dangerous incidents that some organizations see as nothing more than bonding.

Caption: Hank Nuwer, a journalist and college professor, showcases the database of hazing incidents he’s compiled in a classroom on the campus of Ball State University in Indiana.

“Hazing, unfortunately, does bond people together,” he said. “It gives them a quote unquote family. They even call them big brothers, big sisters or dads, mothers.”

Big brother events, in which a member of a fraternity gives a bottle of alcohol to his little brother with the expectation that the pledge chug it, has claimed numerous lives, Nuwer’s research shows.

Texas State student Matthew Ellis died in 2017 after guzzling a bottle of liquor during a Phi Kappa Psi pledge event.

Florida State student Andrew Coffey also died in 2017 after drinking a bottle of whiskey from his Pi Kappa Phi big brother.

The deaths of Coffey, Piazza, LSU’s Gruver led to criminalizing hazing in Florida, Pennsylvania, New Jersey (Piazza’s home state), and Louisiana.

But Nuwer doesn’t think the state laws are strong enough to curb hazing.

“It’s very difficult sometimes to get them written because, number one, the definition of hazing is debated,” Nuwer said.

The laws in Indiana and Mississippi, for example, only define hazing as an act that creates a substantial risk of bodily injury. In North Carolina, it is defined as subjecting another to physical injury.

Other states such as Pennsylvania and New Jersey specifically list actions that constitute hazing including whipping, branding, forcing exercise, and depriving sleep, for example.

Nuwer said that he has seen situations in which lawmakers actively fight against reforms because they were in a fraternity or sorority.

“In Georgia. . . a legislator wanted to pass the law but exclude his fraternity, which is, you know, absurd situation,” Nuwer said.

Georgia’s law makes hazing a misdemeanor of “a high and aggravated nature” for activities that endanger or likely will endanger the physical health of a students through pressure to consume food, liquids, alcohol, drugs or other substances.

It’s named for LSU’s Gruver, who grew up in Roswell, Georgia.

The price of acceptance can be demeaning, dangerous and deadly

While hazing deaths make headlines, thousands of other students are subjected to humiliating and/or dangerous activities.

InvestigateTV and its reporting partner the Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism at Indiana University requested reports of confirmed hazing cases from the 46 largest public and private universities that are required by their states’ laws to make them public.

The incidents included:

· New members of a spirit group at the University of Texas that had to bite off the head of a live hamster.

· Pledges to a Texas State fraternity who were ordered to jump off a roof, paddle each other and fight.

· Pledges to a Georgia Southern fraternity who were required to buy condoms and other sexually-oriented items that totaled between $4,000 to $5,000.

· An Old Dominion fraternity in Virginia that required pledges to pour hot sauce down their pants to simulate a sexually transmitted disease.

· A historically black sorority that was expelled from Bowling Green State University in Ohio after forcing pledges into acts of servitude and consume alcohol, among other things.

“They all think they’re invincible and that nothing bad is going to happen,” Mrs. Piazza said. “But it can happen in in a split second. You cannot predict what’s going to happen with hazing.”

Nine states require colleges and universities to make public reports about each hazing case including the date of the incident, a description of what happened, the date the organization was found responsible by university conduct boards and the sanctions imposed. Oregon requires its schools to report to the state legislature.

That type of transparency was something that the Piazza’s pushed for in the anti-hazing laws in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Jim and Evelyn Piazza stand with New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy following the signing of anti-legislation named in honor of their son, Tim, who died after a hazing incident in 2017.

But not a single state law requires these universities to detail injuries and/or deaths associated with hazing as part of their required reporting. And the public reports often don’t include the information that is required by law.

“You need to know what organization, when it happened, how often it happened. Did it happen last year and then the year before? What were the repercussions? Were these organizations sanctioned?” Mrs. Piazza said.

Ultimately, InvestigateTV either received records or found hazing reports online for 35 schools involving 342 incidents where a student organization had been disciplined by the university.

Seven schools said they had no records related to confirmed hazing cases. The remaining four schools either declined to produce the records or had yet to comply with the request.

The 342 reports analyzed by InvestigateTV show that hazing is predominantly a problem reported with fraternities, which account for more than 75% of the incidents.

InvestigateTV wanted to look for patterns with alcohol, physical or sexual abuse used in the hazing incident. But, in nearly 40% of the cases, the schools did not provide details other than to report that hazing had occurred, despite laws requiring that information.

· But alcohol was specifically cited as a factor in 123 cases. Some forced pledges or new members to consume alcohol at a rapid pace or encouraged underage drinking.

· In 119 cases, the hazing involved some sort of physical abuse such as forcing pledges to do calisthenics, submitting them to sleep deprivation or making them eat non-food substances.

· In 70 cases, student organizations were punished for making pledges run errands, clean the house, act as personal Uber drivers or other acts of servitude.

· Eleven cases put pledges in compromising or sexually-charged situations.

· Universities suspended the organizations in about a third of the cases, with suspensions ranging from three months to 15 years in one especially egregious case.

· Officials banned 11 groups from operating on campus.

Since their son’s death, Piazza’s parents have pushed for state and federal laws to address hazing and for campuses to be open and transparent about those cases.

“We’re looking for the deterrent factor,” Mrs. Piazza said. “And unless there are repercussions, people are going to continue to do this criminal behavior.”

“Someone we know is non-responsive”

A year after Timothy Piazza died, tragedy struck another family.

In 2018, Collin Wiant, a fraternity pledge at Ohio University collapsed and died after inhaling nitrous oxide. His family began advocating for an anti-hazing law in Ohio.

But their efforts dragged for years. It wasn’t until 2021 that the state legislature enacted Collin’s Law. By then, another Ohio family had buried a son after another hazing incident.

“Wood County 911,” the dispatcher said as she answered the call.

“Someone we know is non-responsive. He drank alcohol, like a lot of alcohol,” the female caller told the 911 dispatcher.

The harrowing 911 call from Stone Foltz’s friends on March 4, 2021 details the futile effort to save his life.

Just an hour before, Foltz had been at an initiation event at the Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity at Bowling Green. There, according to his family’s lawsuit, he drank an entire bottle of Evan Williams bourbon in about 18 minutes.

Fraternity members took the passed-out Foltz home. His roommate came home soon after and found Foltz face down on a couch. He called Foltz’s girlfriend to the apartment.

When she arrived, Foltz was barely breathing, according to the 911 call.

“Do you see his chest rising at all?” the dispatcher asked the frantic girlfriend.

“I don’t see it rising,” she screams into the phone.

Foltz died three days later. His death prompted Ohio lawmakers to finally act on the anti-hazing bill created because of Collin Wiant’s death in 2018.

A picture of Bowling Green student Stone Foltz is shown on the university’s football stadium during a memorial following his death from a hazing incident in 2021.

Those who push for stronger laws both at the state and federal level wonder how many deaths are too many.

Hazing deaths have prompted at least 11 states to enact laws in the name of the victims.

There’s Jack’s Law in Arizona, named for Jack Culolias, a fraternity pledge who went missing after a night of drinking and later was found dead in a river in 2012.

There’s Matt’s Law in California, named for Matthew Carrington, a Chico State University fraternity pledge who died from water intoxication after being forced to drink from a 5-gallon bucket that was repeatedly refilled.

There’s the Tucker Hipps Transparency Act in South Carolina, named for the Clemson University fraternity pledge who fell from a bridge into a lake and died.

Sen. Cassidy introduced the federal End All Hazing Act, which would require all colleges and universities to publicly report and post hazing incidents. The bill has bipartisan support, with parents and Greek organizations also on its side. Yet movement on the bill is stagnant.

More recently Sen. Cassidy joined bipartisan lawmakers in introducing the REACH Act, which would establish a specific definition for hazing and include those incidents as part of a university’s annual crime report

“They need to be proactive instead of reactive because we can’t wait for a child to die in every state in order for legislation to be changed,” Mrs. Piazza said. “And it’s a lot of work for the parents that are doing this work to take care of this.”

And they are parents who are grieving.

“Hazing is always an intentional, damaging act,” Mrs. Piazza said. “It is not something to be treated lightly. It’s not boys will be boys. It’s bad. It’s really bad and it can progress.”

Hazing, masked as sacred rituals, has claimed many boys: Timothy, Matthew, Adam, Collin, Stone, and so many others.

FRATERNITY AND/OR UNIVERSITY STATEMENTS

Meredith Hemphill, Ryan Murphy, Maddie Maloy, Julia Pearl, Mackenzie Lionberger, Tatum Hanson and Ashton Hackman are with the Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism at Indiana University.